We ask Paul Alsop, a current student of Albert Watson’s online photography course and an artist of wet plate portraiture, a few questions about his life and career, his use of this unusual technique and what he’s gained from studying Albert’s course.

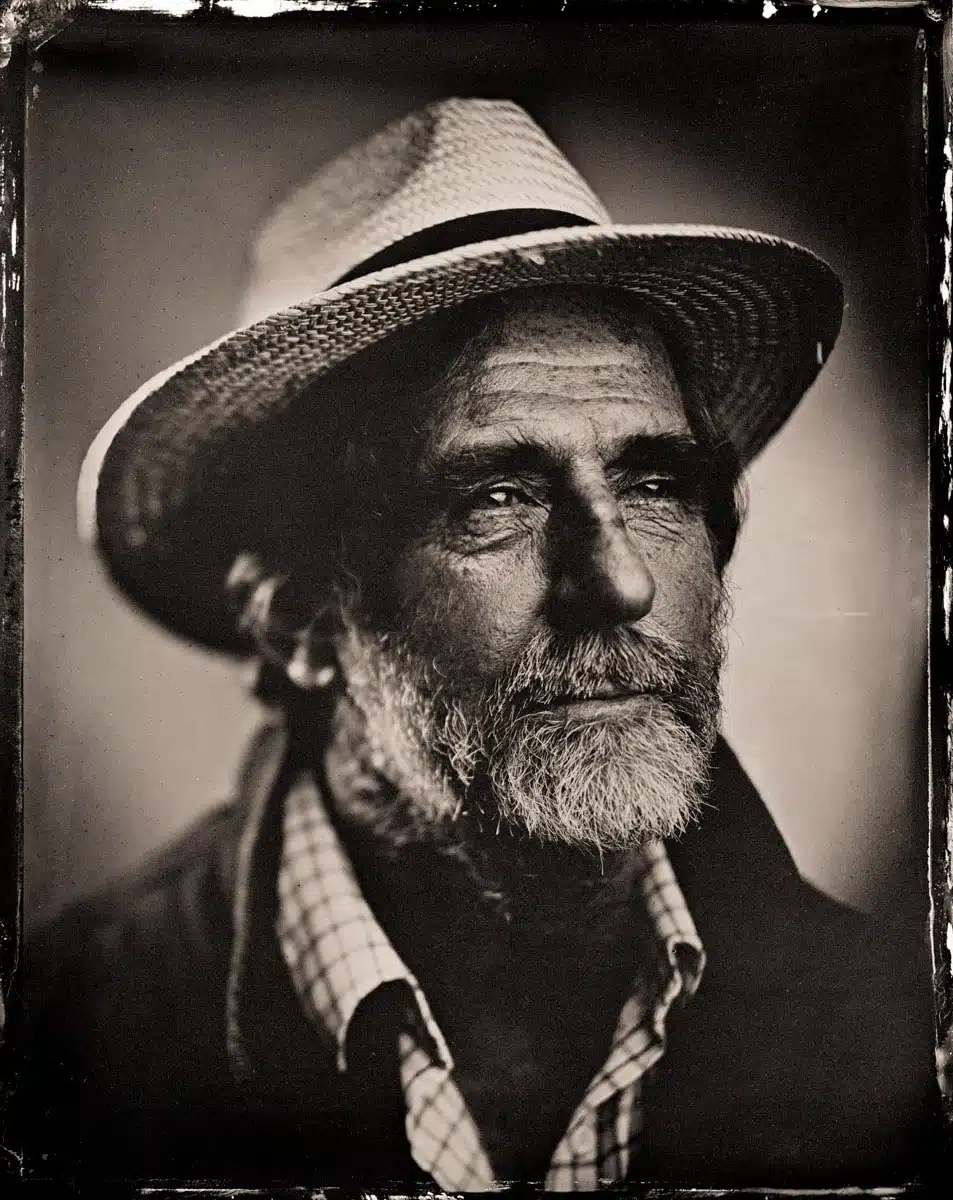

Paul Alsop by Luke White

1. Hi Paul, can you tell us a little bit about yourself, your personal background and your style of photography?

Kia ora, thanks for the opportunity to write about my journey and work with photography.

My name is Paul Alsop, I am a 40-year-old bloke from Newcastle upon Tyne in the UK but have lived in the Bay of Plenty, New Zealand for the past 11 years. My occupation is that of a family doctor, a role in which I see many, many faces on a day-to-day basis, perhaps one of the subliminal reasons I enjoy portraiture so much. I like raw portraits, ones that make you feel like you can reach out and touch them. I refer to myself as a ‘wet plate portrait maker’, at a push I might call myself an ‘artist’ rather than a photographer. I have an issue with semantics around the term ‘photographer’ – if I was to call myself a photographer, I would have to pre-face it with the kind of photographer I am. People in the past have asked are you an amateur or professional? I always struggled to answer that, as the delineation of amateur vs pro is technically whether or not you make a living from photography, however, the term has evolved to be a reflection of the quality of work rather than source of livelihood. We all know some pro photographers that make a living from photography but produce low quality work, and vice versa.

This is probably part of the interview where I start talking about COVID-19 and how it has had a personal impact on my photography. As I’ve said before, I work day to day as a doctor and over the past 18 months pretty much all of my waking energy left over from doing the day-to-day work has been given to thinking about COVID-19. On reflection, I feel I’ve wasted a lot of my creative energy on COVID-19 that I could have put into making portraits, because in New Zealand, we have been very very lucky in avoiding significant disease burden up until the past few weeks, where we have now joined the rest of the world pandemic statistics.

2. How did you get into photography? Was there anything in particular that you remember that made you want to be a photographer?

I would love to give you a romantic story about how my grandfather handed me his well-used Leica at the age of 8, and I’ve been hooked ever since. The truth is less romantic, the truth is…. fish. Yes, fish.

As a medical student, in about 2002 I started keeping tropical fish in the UK, as with most things I do, this quickly evolved into something a lot more complicated than it should have been, and I found myself with a tropical marine, coral reef biotope tank with flamboyant shrimp, exotic corals, and some really interesting goings-on. I was part of an internet forum, and I wanted to show off my creation. I had an automatic point and shoot camera at the time, every time I tried to take a photo, the flash would go off and the tank would look black and lifeless, to cut a long story short, I had to learn how to use a camera. A year or so later, I bought my first ‘real camera’, which was a prosumer camera, a ‘Fujifinepix’ or something. I quickly reached the limits of this, and I bought my new DSLR a few months later, a Canon 30D. Photography started to take over, I had got all the excellent pictures of my fish tank (only so many angles you can photograph a tank) and I moved out into the landscape to practice a bit more, I would often be found roaming the Northumbrian countryside, hunting the perfect sunrise at 4am in the morning. I had learned how to use a camera in the preceding 18 months and although I wasn’t aware of it at the time, on reflection, it seemed I had the ‘photographer’s eye’ a natural ability to find good composition in a photograph, without really thinking about it formally.

As with most aspects of my life, I have to know everything about what I am doing, learning to use a camera in manual mode was just the key that unlocked the door to the vast universe of photography. I started to learn about composition, colour theory, the history of photography, I would spend hours in second hand book stores, looking for for books to buy, mainly books authored by famous photographers (I had a hit list): Martin Parr, Robert Frank, Cartier-Bresson to name only a few – all very interesting and I was like a sponge. I was still a medical student, I’m not sure how much brain power I diverted away from my studies to absorb the world of photography. In particular, I remember, this like it was yesterday:

I was sitting in an 18th Century bookshop in Carlisle, UK. The big old building was built of sandstone bricks, with small narrow windows, it was dark and dusty and you could often see the dust in the air highlighted by shafts of light from the small narrow windows, it was a rabbit warren with a cellar and 4 floors, packed with old used books I remember, sitting on the stairs where the photography book section flowed out onto, with people stepping over me as I thumbed through a book called Red Heads by Joel Meyerowitz – I fell in love with portraiture at that point.

As time passed by, and I moved to work in New Zealand in a small hospital in a place called Thames, my continued interest in photography was raging, I’d travelled across North America, and through Australia to get to New Zealand over a period of 6 months, I photographed the landscapes, the Wildlife, the humans of Canada and Alaska. My interest and passion for photography continued to grow, I got some interest from NASA, who featured one of my images of Aurora Borealis in their ‘Picture of the Day’ sections, my image was sandwiched between a picture from the Hubble telescope the day before and a picture from the Mars Rover the day after which was a highlight of my travels for sure!

As I became settled in New Zealand, and working in a rural hospital, I started looking more and more into the history of photography and in particular, analogue film photography. I used to find myself sitting at a computer, ‘pixel peeping’ retouching blemishes and eyes, often so close to the detail, to lose the overall bigger picture of what I was working on. It was this frustration for perfection that drove me to look at less digital ways of making images. On a medical ward round at the hospital I was working at one day, I snuck away to see the head of maintenance of the hospital and the premises. I wanted to see if he had any old benches or stable tables to put an enlarger I had found at the local dump on, for the home darkroom I had planned. He told me he could do better than that, give him a week. A week later, he handed me keys to a padlock for a room in the hospital boiler building, he and his team had blocked out any light leaks in the room, installed a series of beaches, a water still, some old radiographic light boxes and red lights! I had my very first own darkroom and I went to town on it, making mistake after mistake, wasting chemicals and a lot of glorious time learning from my mistakes on how to process film and printing. I would often miss my lunch breaks at the hospital, so I could ensure I’d finished all of my ward tasks (keeping patients alive) so I could leave on time, instead of going home, I’d go to the darkroom and waste time, often saying beyond midnight, then back on the ward again in the morning for 7am.

On reflection, I think I probably did the film thing at the wrong time, film was starting to become hard to buy and wasn’t enjoying the ‘trendy’ revival it is now. As I worked and lived in a small rural town, I had to get all of my chemicals couriered to me, which was expensive and took time. I wondered more and more about DIY options for making images. It was at this same time in about 2013 my mind was starting to wander and think about what I could do next with photography, that I ‘stumbled upon’ a nude diptych of Kate Moss by Chuck Close, it was one of the most beautiful things I had ever seen. It was a daguerreotype, two highly polished copper plates, to produce a ‘warts and all’ portrait of Kates top and bottom half of her body, it was incredible, unlike most of the airbrushed digital images I had been used to seeing, this was detail+++ you could see the pores of her skin. After a quick Google, it took me about 30 mins to realise the daguerreotype process was pioneered in 1839, used mercury vapour to expose the image, I felt a bit deflated, knowing how neurotoxic mercury is, and knowing it was the cause of ‘Mad Hatter’s Disease’, I realised I could never make images as raw as that. However, after a bit more research through this history of photography, I fast forwarded to 1851 and found the ‘Wet Plate Collodion process’ – the only dangers of this process is that it was highly explosive and you had to work with carcinogenic heavy metals, perfect – no madness on the cards here!

After researching “Wet Plate Collodion in New Zealand” I found only one active practitioner of the process, Brian Scadden, he lived in the South of the North Island of New Zealand, and had been active with the Civil War re-enactment photographers from the USA which had pretty much kept the process alive. I asked Brian if he could make a wet plate portrait of me and my wife, we went to visit him for the portrait, and within a few months I was back again to learn more, after a 2 day workshop I felt I had a good grounding in the process to go off and teach myself the wet plate process. Problem number 1 (there were many as it turns out, but this was a big one) – I had no camera that I could make ‘plates’ with, typically you use a large format camera, 4×5 or larger, and most of these cameras were found in the USA/Europe with exorbitant import charges due to their weight. I’m never one to be beaten by a hurdle, so I decided to get some wood and brass and build my own 11 x 11″ bellows camera, which was my workhorse for the early years, before a trip back home to the UK saw me come back with large format camera from the 1970s and 1890s which I use a lot more these days.

3. Choose 3 of your own photographs and tell us about them.

The first (at the top of the page) gives some historical context of my journey, and is a portrait of myself taken in 2014, by Luke White. Luke was a manager of the largest photographic studio in New Zealand at that time. The nature of the very light insensitive wet plate process means that you either need very long exposure times to make a portrait (10 to 30 seconds) or some very strong lights. I was frustrated by the blurry images I was getting from longer exposures, I wanted that ‘Kate Moss’ detail I spoke of before, unfortunately, even clamping a sitters head into a ‘vice’ for a portrait, there was still blinking and sway with natural light long exposures. Thinking outside the box, I contacted Kingsize Studios in Auckland to ask if they had any ideas where I could get lights powerful enough to render a strobe image on a wet plate working with an ISO of about 0.5 to 2, I was very fortunate to contact Luke, as he also was interested in the history of photography and invited me to do some light testing in Auckland with some heavy hitting 3200 w/s Broncolor packs and heads. After a few failed attempts, Luke took this portrait of me and I did one of him. On reflection of that day, we didn’t know it was history in the making – there had never been a successful attempt in New Zealand of making a Wet Plate portrait with artificial light – we were trailblazers in the making!

Portrait 2 is of my daughter who was 3 at the time. Any wet plate photographer will tell you there are inherent difficulties taking portraits of children for a few reasons:

a) you only get one chance to make 1 image – the strobes are so very powerful (an explosion of light at 3000/6000/9000 w/s), they rarely come back for a second portrait

b) they move a lot and it takes about 20 minutes to make one portrait, so there is a lot of messing about with lights, chemicals etc.

c) the depth of field is incredibly narrow, so getting them in the plane of focus in one shot is either very skilful, or very lucky! (I like to think its the former).

This portrait of my daughter was only the second portrait I’d make of her in her life (with wet plate), her eyes were nearly bigger than her head, she was old enough to obey commands of “stay very very still and daddy will get you a bar of chocolate” – I hadn’t counted on the resultant harrowing image that was produced, I couldn’t stop staring at it. There is a child in the portrait, but there is an underlying notion that she may at any point, reach out of the image and stab you in the head – “beautifully haunting” I’ve had it described as, “like something from “Miss Peregrines Home for Peculiar Children”.

The third image is also one of my children, I made it when he left Kindergarten for Primary School. As part of New Zealand culture, the children are held in great respect, and at his leaving ceremony for Kindergarten, he was draped in the traditional New Zealand Korowai (a feather cape, that infers the wearer holds great ‘Mana’ or respect). He wore the Korowai for his portrait, and I constructed the image as a tribute to reflect the ‘Mana’ (authority/prestige) he had developed in the first 4 years of his life.

4. Can you tell us a little more about the wet plate technique?

‘Wet Plate Collodion’ is a historic photographic process that was pioneered and used in the In the mid to late 1800’s by an English photographer called Frederick Scott Archer. It is the third oldest form of photography, preceded only by the Talbotype and the Daguerreotype which were invented only twenty years earlier. The process is ‘wet’, made with an explosive chemical called collodion, which is a mix of gun cotton, alcohol and ether, the mixture is made light sensitive when it is immersed in a bath of liquid silver. As I’ve said previously, in 2014, I contacted Luke White to see if it would be possible to adopt a contemporary approach and use of modern lighting. Up until this point, I had been making portraits with natural daylight. The process is very light insensitive, having an ISO of approx. 0.5 to 2, which meant I was making portraits in harsh ugly light with exposure times of 2-5 seconds, or open shade and exposure times of 10 seconds plus. The output is a physical image made on a piece of glass or metal, ‘Ambrotype’ and ‘Tintype’ respectively.

As the process needs to be ‘wet’ if the plates dry out, they are useless meaning they need to be developed immediately after the exposure is made. Over the years, I’ve converted a hospital boilerhouse, my garage, a retro 1970s caravan and more recently a shipping container into a darkroom. Each plate is one of a kind, never to be replicated and as archival as we know – they don’t fade like paper prints do, plates of Abraham Lincoln and Billy the Kid are still around to view.

If you look at most of my portraits, you will see my thumb print in one of the corners. This is a by-product of the hands on-nature of the process, it’s simply where I hold the plate during development.

5. Why did you choose to study Albert Watson’s online photography course?

Unconsciously I’ve always been a fan of Albert’s work, his photographic portfolio is so very wide and varied, I’ve often fallen in love with his images and did not realise it was an Albert Watson until I went on to research the author of the image. Again, to reflect back on Kate Moss, there are some iconic images of Kate Moss by Albert, so much variation and quality in the images. I actually thought Albert and Kate had worked together for most of their careers, I was blown away to hear Albert say he had only worked with her on one occasion for one day in Morocco and the output was the diverse portfolio of images.

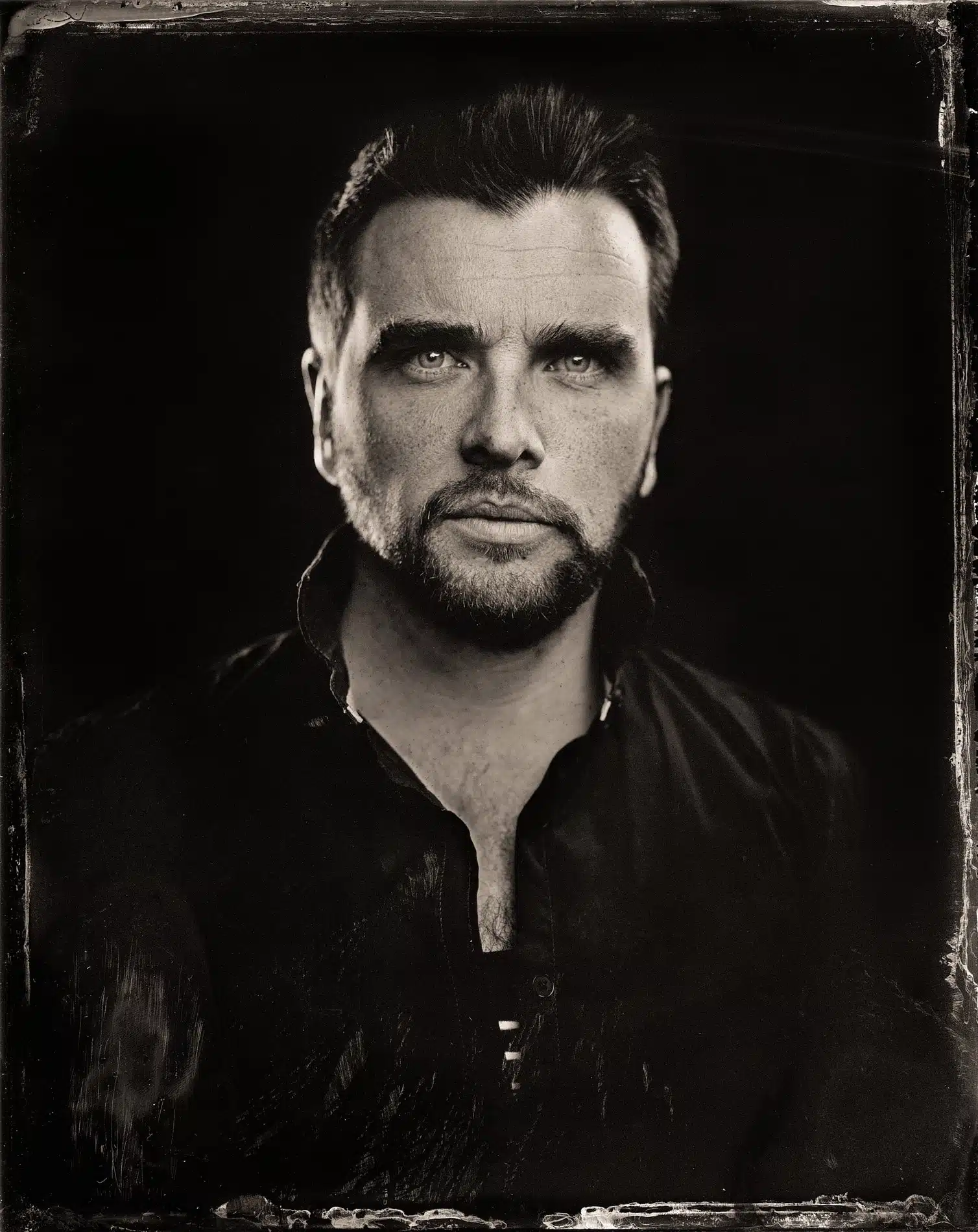

I’ll include another image if I may, it was a direct tribute to an Albert Watson portrait of Sean Connery. Making a wet plate portrait takes 20 minutes, and A LOT of planning (often weeks), especially with lighting – I pretty much get one attempt at making an image. I love the depth of the portrait (2003 I think) and I used the image to deconstruct the light for a portrait of a local farmer of South African descent living in New Zealand for many years called Jan. He had so much character in his face, and I felt the portrait needed to reflect this. As you will see the lighting was deconstructed (I searched but couldn’t see any lighting plan references for this image, so I had to reverse engineer the light – this is always tricky, especially when doing tests with liquid silver, as every exposure costs a lot of money to produce.

6. What is the most important thing you think you’ve learned from the online photography course?

As you may appreciate, I’m still working my way through it, again, COVID-19 work and general doctor work keeps distracting me, however, when I saw MoP were promoting an in-depth series of interviews with Albert Watson I was frothing to sign up. I recently had a few days annual leave at a beach house, so I smashed quite a few of the lessons while sitting looking over the South Pacific Ocean. I’m about halfway through. I think I have quite a good grounding in the technical aspects of photography and lighting (although I’m always keen to learn tips and tricks from the professionals) for me, I’ve been enjoying the lessons that describe the shoots and interactions with some of his most famous subjects (Kate Moss and Alfred Hitchcock).

Thanks so much, Paul!

You can see more of Paul’s work on Instagram, on Facebook on on his website. Have a look at Albert Watson’s photography course to see one of Paul’s many sources of inspiration or to see the work of other students, check out the Masters of Photography Photostream.

Get 7 amazing free lessons from the Masters

Each complete lesson is packed full of tips and tricks from some of the greatest photographers in the world

If you’d like to learn more about all our Masters Of Photography, then why not join up to our Free Online Photography Courses, where you can trial some content for FREE before you enrol in a photography course. You'll get a lesson from each our Masters: (Albert Watson, Cristina Mittermeier, David Yarrow, Joel Meyerowitz, Nick Danziger, Paul Nicklen and Steve McCurry!). They'll cover a number of genres of photography including landscape photography, street photography, fine-art, sill life, fashion, travel photography, conservation photography, wildlife photography and much more.