10+ Essential Questions Answered by the World’s Most Respected Photographers

Learn how the world’s best photographers shoot, think, and create — and how you can too.

Above: Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark. – A veiled chameleon, Chamaeleo calyptratus, confronts a camera lens at Rolling Hills Wildlife Adventure, Salina, Kansas, 2007.

Photographer Spotlight: Joel Sartore

Speaker, author, teacher, conservationist, National Geographic Explorer, and a regular contributor to National Geographic Magazine.

Joel Sartore is a photographer, speaker,author, teacher, conservationist, National Geographic Explorer, and a regular contributor to National Geographic Magazine. His hallmarks are a sense of humor and a Midwestern work ethic. Joel specializes in documenting endangered species and landscapes in order to show a world worth saving. He is the founder of the National Geographic Photo Ark, a multi-year documentary project to document every species living in zoos, aquariums and wildlife sanctuaries, inspire action through education, and help protect wildlife and their habitats by supporting on-the-ground conservation efforts.

“It is folly to think that we can destroy one species and ecosystem after another and not affect humanity. When we save species, we’re actually saving ourselves.”

Portrait of Joel Sartore, 2021, by Ellen Sartore

Joel has produced many books including RARE: Portraits of America’s Endangered Species and Photo Ark Babies. His photography and writing have appeared in major outlets including National Geographic, The New York Times, and Audubon Magazine. His work has also been featured on numerous national broadcasts such as 60 Minutes, CBS Sunday Morning, NPR, and PBS documentaries, including the series RARE: Creatures of the Photo Ark. Joel is always happy to return to home base from his travels around the world. He lives in Lincoln, Nebraska with his wife Kathy.

Q&A with Joel Sartore

Vision & Purpose

What is your ultimate aim in photography? What are you hoping to express or achieve through your work?

Photography is a powerful way to tell meaningful stories. Through the National Geographic Photo Ark, I hope these portraits tell the stories of species all around the world, showing animals that might not otherwise get attention if it weren’t for these photographs. We seek to show just how stunning each and every one truly is. The Photo Ark is a multi-year effort to document all species living in the world’s zoos, aquariums and wildlife sanctuaries; inspire action through education; and help protect wildlife by supporting on-the-ground conservation efforts.

So many of the species I’ve documented in the Photo Ark are disappearing at alarming rates due to a number of manmade pressures, like habitat loss, pollution and climate disruption. I hope my portraits encourage people to look each of these animals in the eye and see that they’re so worthy of our attention and protection. In the end, I hope the Photo Ark isn’t simply a record of all the animals we’ll lose to extinction, but a testament to the ones we can save while there’s still time.

“Today we are losing species at rates 1,000times greater than ever before.”—Joel Sartore

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark. A Florida panther, Puma concolor coryi, at Lowry Park Zoo, Florida, 2012.

How do you hope your photographs make people feel? Is there a particular emotion or response you’re often aiming to evoke?

At the heart of the Photo Ark is a mission to inspire people to care about wildlife conservation and know that there’s still so much we can do to help protect wildlife. Oftentimes, it can be incredibly difficult to think about the species we’ve already lost, or the ones I’ve just photographed that may not come back from the brink of extinction. What if I’m too late in getting the public to care about this animal before it vanishes? But the Photo Ark isn’t about darkness – it’s about hope and trying our very best to inspire change. It’s about the power of people coming together to make a difference, not just for one animal but for all of them, and ultimately us too. When people look into the eyes of the animals in my photos, I hope the spirit of resilience resonates with them and inspires them to care about all creatures, big and small.

“I want to get people to care, to fall in love,and to take action.”—Joel Sartore

Inspiration and Influence

Which books, exhibitions, or fellow photographers have had the biggest impact on how you see the world through your lens?

When I was growing up, my mom had a set of Time-Life picture books. In one that was called “The Birds”, there were several passages about birds that had gone extinct, and one bird in particular really resonated with me. Her name was Martha, and she was the very last passenger pigeon before the species went extinct. The photo I was staring at was taken of her alive before her death in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. I couldn’t fathom how a bird like Martha, part of a species that had an estimated population of five billion, could dwindle down to just one, before vanishing all together. It was this moment that ignited my passion for wildlife conservation and the question that guides my work today: what can I do to protect at-risk species? It was this sort of natural pairing – my love of wildlife and my passion for photography – that allowed me to bring these two interests together in such a meaningful way for me.

There are so many animals like Martha who existed way before our time but are no longer around. There’s very little, if any, documentation of these animals – it’s usually grainy, black and white stills. The Photo Ark is my way of giving each of these animals their moment in the sun. It’s also an invitation for viewers to peer through my lens to see the beauty and wonder of species they may never have known existed.

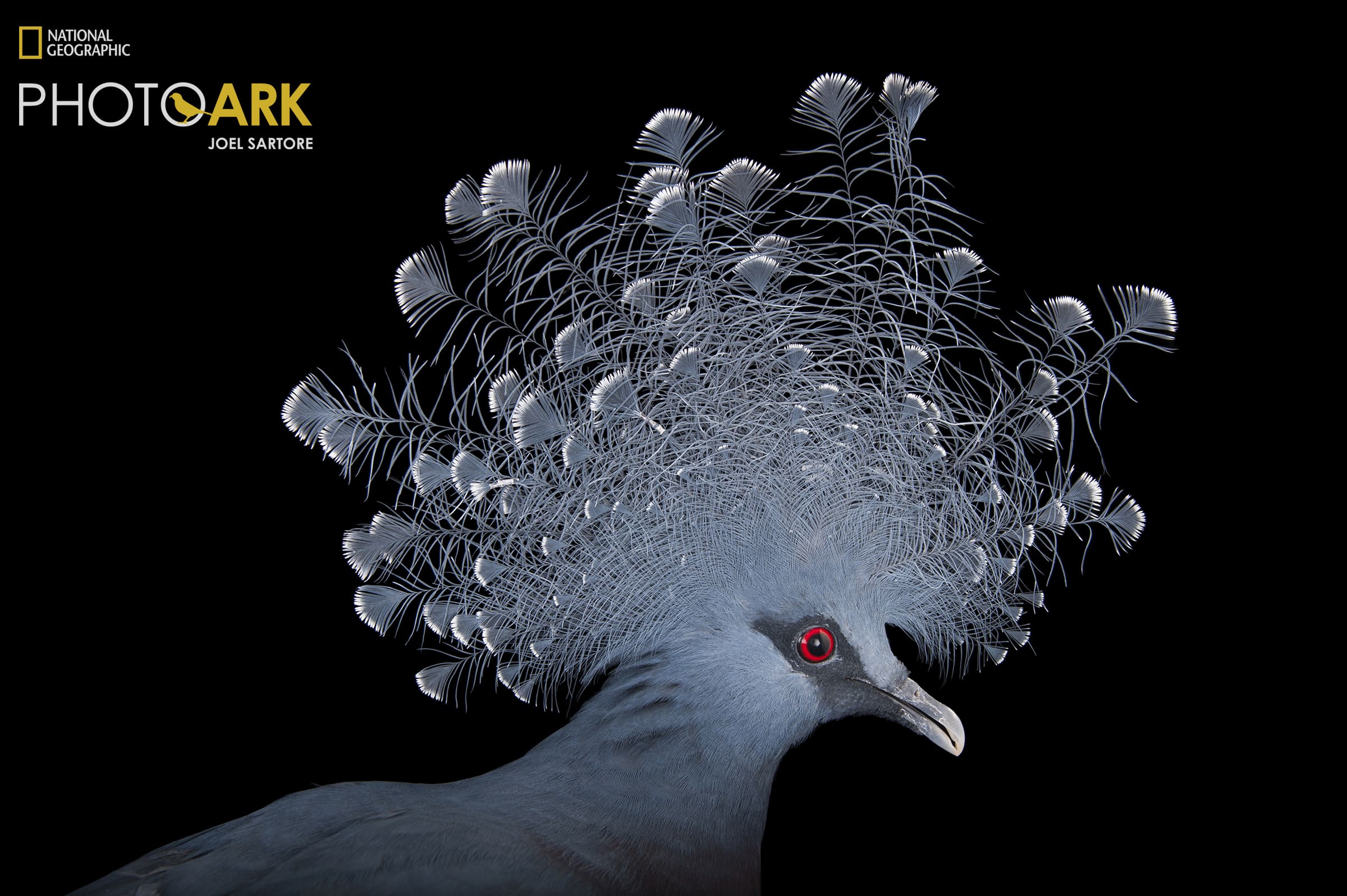

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.A Victoria crowned pigeon, Goura victoria, at the Columbus Zoo, Ohio, 2012.

Many photographers strive to develop a unique style or voice. What practical steps helped you discover your own, or do you believe a distinct style is even necessary?

The style of the Photo Ark came to me in a very organic way. I had been on the road for years with National Geographic magazine, photographing animals in all sorts of natural environments, such as brown bears fishing in the rivers of Alaska or koalas clinging to trees in Australia. In 2006, those travels came to a halt when we learned my wife was sick with cancer and so I was home for a year caring for her and our three small children. As Kathy’s health improved (she’s just fine today, thankfully) I began looking for things to continue photographing, but in my own backyard. I went over to the Lincoln Children’s Zoo, just a mile from my house, and the zookeepers brought out a naked mole rat on a white cutting board – something to eliminate background distractions and allow me to focus only on the animal in front me.

That’s the genesis of the Photo Ark’s style and why every species that’s a part of the Photo Ark is documented on a black and white background. Without distractions and size comparisons, a beetle becomes the same size as a tiger, emphasizing that all animals are vital to wildlife biodiversity.

Process and Practice

Can you walk us through the story and techniques behind one of your favorite photographs? What makes it stand out to you?

Bonobos are the closest living species to humans and Kanzi, the bonobo, was brilliant – a Rosetta Stone, linking human and ape communication. I had the honor of meeting and photographing Kanzi in 2019.

We went to work setting up until we had a large, empty white space. Generally, we shift primates in with snacks, but all of the staff was next to me, on the other side of the glass. I looked over and asked what the plan was and they said, oh Kanzi is coming. I asked them how they knew and they told me they’d asked him to join us. Sure enough, a moment later, Kanzi strolled in and sat on the white background, though he faced the wall instead of me. “Kanzi,” said the staff, “can you turn around?” Casually, Kanzi looked over his shoulder and then pivoted to face me. It went on like this for the whole photoshoot. Kanzi stood or sat at request and modeled like a superstar. It was amazing. If only all of my shoots were this easy. At the end, we rigged a system with a button and Kanzi took a photo of me; it’s the only time I’ve been photographed by anything besides a human. It was a surreal and wonderful moment.

An endangered (IUCN) and federally endangered bonobo (Pan paniscus) named Kanzi at the Ape Cognition and Conservation Initiative (ACCI) in Des Moines, Iowa. Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

Kanzi modeling like a superstar. Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

Photo of Joel Sartore by Kanzi, endangered bonobo (Pan paniscus) at the Ape Cognition and Conservation Initiative (ACCI) in Des Moines, Iowa. National Geographic Photo Ark.

What photographic—or broader artistic—technique do you find yourself returning to most often, and why?

The studio portrait technique is the hallmark of the Photo Ark and I made it this way for several reasons. First, there are a number of species that don’t exist in the wild anymore without the help of human care. Shifting these animals safely onto black and white seamless backgrounds allows us to concentrate intensely on each species, focusing on their intricate details and expressions and ultimately raising awareness of the plight of endangered species.

Another reason for the studio portrait is to give each animal equal space. Some of the frogs I’ve photographed are the size of a thumbnail, and this is a way for me to put them on equal footing with bigger animals. There’s also a practicality to studio portraits. When I head out on a shoot, I know I’ll see the animals I’m photographing because I’ve already arranged with the facilities to do so. In the wild, it’s not guaranteed. So, I find this approach not only assures that I’ll document the species I still need, but also allows me to bring a distinctiveness to these animal portraits that you don’t find elsewhere.

How do you personally recognize when a photograph you’ve taken is truly great? Whatdo you look for?

I don’t think of my work as great. I see it as the result of a lot of work. By putting myself in front of so many animals, eventually this has turned into a body of work that, hopefully, will inspire the public to care, and actually do something to help the natural world.

All that said, working with animals can be unpredictable, and since their safety and care is our highest priority during a photoshoot, sometimes I may not get all the shots I want because I don’t want to cause the animal any stress. You can’t really tell a bear to sit still, so I take whatever I can get, trying to be flexible throughout the process. The best photos involve eye contact with the animal, which in turn helps people connect with things they may not know much about. In my experience, connection leads to caring. A photograph that allows someone to look deeply into the eyes of a subject gives us our best chance at engaging the viewing public.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark. An endangered baby Bornean orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus, with her adoptive mother, a

Bornean/Sumatran cross, Pongo pygmaeus x abelii, at the Houston Zoo, Texas, 2013

Gear

What’s a piece of gear you didn’t expect to love—but now never leave behind?

My backup equipment! Most of the time, there’s no camera store where I’m going, so I always carry duplicate camera bodies and lenses, lots of batteries, cords and cables. That may make for extra baggage, but I’d rather be hauling more than enough equipment than miss an opportunity to document a particular species I can’t find anywhere else.

Joel Sartore photographs Johnny the serval, Leptailurus serval, at the Lincoln Children’s Zoo,

Nebraska, 2018. Photo by Cole Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

Joel Sartore with frill necked lizard, Chlamydosaurus kingii, at a high school in Victoria, Australia,

2017. Photo by Douglas Gimesy.

Joel Sartore carefully photographs a dwarf caiman, Paleosuchus palpebrosus, at the Sunset

Zoo, 2011. Photo by Cole Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

Growth

Was there a particular mindset shift, technique, or experience that accelerated your learning more than anything else?

I think the single greatest mindset I’ve adopted to help get me where I am today is persistence, not only in the persistence it takes to get the right shots, but to get those photos seen and the stories told about each and every species.

I got into photography late in high school after borrowing an old Olympus camera from a friend’s dad. From there, I went to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where I eventually found my way to majoring in journalism. I worked at a newspaper in Wichita, Kansas, for about six years, which is where I met James Stanfield, one of the legends of photography at National Geographic. He encouraged me to submit my work to National Geographic, and so for two years, I sent in my clips until I got that call for my first assignment. One turned into two, which turned into three, and now here I am with over 47 stories in National Geographic magazine.

In my persistence to get the next call, I worked like crazy on those assignments—and each one since—doing everything I could to make sure the photos were as good as they could be. All of those experiences in the field and on assignment shaped me into the person I am today.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark. A Saint Vincent parrot, Amazona guildingii, at the Houston Zoo, Texas, 2015.

When you hit creative blocks or feel uninspired, how do you push through? Do you have any personal strategies to reignite your vision?

For me, it all comes back to our mission: to get people to care about the world’s animals and the habitats they need to survive. I’m fortunate in that all my current work is part of this larger goal to document at least 25,000 species living in human care around the world as a means of inspiring people to protect them. When I’m frustrated during a shoot or tired from all the travel, I have the Photo Ark to lean back on and remind me why the work is important: we give a voice to the voiceless.

For photographers who may not have such a foundational mission to turn to, I’d suggest looking internally for the same reasons and ask yourself, why are you doing this and what makes it important to you? I bet that’s where you’ll find renewed inspiration.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark. A giant Pacific octopus, Enteroctopus dofleini, at Dallas World Aquarium, Texas, 2013

Current work

Can you tell us about a recent or past project that you’re especially proud of, and what made it meaningful to you?

The Photo Ark is truly my life’s mission. When I’m older and no longer photographing animals in the far corners of the world, I’ll look back at my life and know in my heart that I did everything I could to help protect Earth’s amazing animals. It’s never too late to get involved in the things you’re passionate about. Will you join me?

Final thoughts…

There’s never been a better time to be a conservation photographer. There are so many stories to tell and through online platforms, we’re able to get the word out like never before. I encourage you to think about all you can do, to the best of your ability, starting today.

To give one’s full measure of devotion to a cause we believe in; if that’s not the very definition of a life well-lived, it should be.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark. A ribboned pipefish, Haliichthys taeniophorus, at Dallas World Aquarium, Texas, 2013

Joel’s story reminds us that photography is more than capturing images—it’s about giving a voice to the voiceless and shining light on the beauty and fragility of life around us. The Photo Ark is a call to action: to look animals in the eye, to recognize their worth, and to fight for their survival while there’s still time. His persistence shows that one person, with a camera and a mission, can spark change on a global scale. For anyone with a passion—whether it’s photography, conservation, or another path—the lesson is clear: pour your heart into what matters most, because your work has the power to inspire hope, connection, and lasting change.

Thank you for reading and if you’ve been inspired by the interview and want to deepen your skills, mindset, and storytelling ability, we invite you to explore our full range of courses — featuring legendary photographers like Steve McCurry, Joel Meyerowitz, Albert Watson, and more. See all our courses here: https://mastersof.photography/

At Masters of Photography, we believe that learning from the world’s best is the fastest way to unlock your own creative voice!